‘Who I was and who I am as a woman, as a world-class athlete, was only because of my mother’s story’

When Canadian hurdling champion Perdita Felicien sat down to write her memoir, she realized that in order to show people who she truly is, she had to tell her mother’s story.

The Oshawa, Ont.-born athlete is a 10-time national champion, a world champion and a two-time Olympian. And after a devastating fall at the 2004 Olympics in Athens, she picked herself up and continued to build an incredible career, both on the track and behind the camera as a sports broadcaster.

But none of it would have been possible without her mother, Cathy Felicien Browne.

“Who I was and who I am as a woman, as a world-class athlete, was only because of my mother’s story and because of who my mother is. And I had to tell that,” Felicien said.

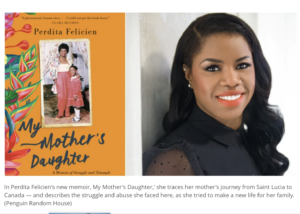

Both women joined As It Happens host Carol Off to talk about Felicien’s new book, My Mother’s Daughter: A Memoir of Struggle and Triumph, which hits shelves on Tuesday.

An immigrant story

Felicien Browne’s story begins on the Caribbean island nation of Saint Lucia. Money was tight when she was growing up, so she often had to skip classes to help her mother. She also sold seashells and other trinkets to tourists at beach-side hotels.

That’s what she was doing when she happened upon the opportunity that would change her life forever.

She saw a man by a pool with a little baby, so she walked up to him, introduced herself, and asked if she could be the child’s babysitter.

He and his wife were Canadian, and they told her that when she turned 20, they would bring her to Canada to work as a full-time child care provider.

She never expected them to keep their promise, but when they did, her parents encouraged her to seize the opportunity.

“My mom offered to … look after my two kids so I could go to Canada and have a better life for myself. And I said to myself, this is the gift that I am going to give to my parents, that I go to Canada and then help them and help myself,” said Felicien Browne.

Felicien Browne worked for that family for a little while.would spend her early years in Canada working for different families — cooking, cleaning and looking after children.

It was a difficult life, and the people she worked for held immense power over her. One of her later employers — called Mrs. Harry in the book — liked to remind her of it.

“Because I was working under contract with her, she was always threatening me that she would call the immigration,” Felicien Browne said. “At that time, I am new in the country … I didn’t know that I have my rights.”

She also recalled the time when she was pregnant with Perdita, and felt stabbing pains in her abdomen. Mrs. Harry eventually offered to give her a ride to the hospital, but first asked Felicien Browne to make some tuna sandwiches.

“Through my life, my mother would say things as I was young and growing, you know, ‘When you came into my life, Perdita, you gave me hope,’ or, ‘You gave me purpose and a reason.’ And I didn’t really understand what she meant,” Felicien said.

“But as you grow old and you gain understanding and perspective, it just became loaded. And I thought, well, what kind of life did mom have? And what kind of hope and purpose did I give her? And it wasn’t until I started to write and I pieced my mother’s life together [that] I saw all the things that she had to endure to give me the experience and the richness of the life that I have.”

But Brown’s biggest obstacle was her husband, Bruce. He was not Perdita’s biological father, but the only dad she’s ever known.

“Usually my dad was upset about something that my mom had done that he didn’t like. Maybe the dishes weren’t washed, or food wasn’t cooked or there’s not enough groceries in the cupboards, even though he didn’t give her a lot of money to buy any groceries,” Felicien said.

Felicien was about six or seven the night things got really bad.

“All I remember is my mom was very pregnant and they were wrestling. They end up falling down some stairs in a heap. My sister calls the police,” she said. “The police get there, and my dad decides he’s not staying. He leaves so he doesn’t get arrested.”

Felicien Browne and her children ended up at the Auberge women’s shelter in Oshawa, now known as Denise House. In many ways, Felicien Browne said, that’s when her real life began.

Later, the shelter helped her move into a townhouse. It was the first time in her life that she knew true independence.

“It opened my eyes. I did things that I thought I couldn’t do. I wanted to make my children proud — went to school, learned how to drive, got a job,” Brown said. “It was not easy for me, but I had to prove to my children and the women that you can fall down three times and then come back up stronger. And that’s what I did.”

‘Go, Perdita, Go!’

As Felicien grew up, it became clear that she had a preternatural talent for athletics, excelling at track and field, and hurdling.

And her mother was her biggest fan.

“You would have to have ear plugs in your ear whenever my mom showed up at the stadium,” she said. “In high school, I was so embarrassed by it that I banned her. I said, ‘You cannot scream this loud for me in the stands. It’s embarrassing.'”

The next time she saw her mom in the stands, she was as quiet as a mouse. But then she unzipped her hoodie revealing a T-shirt underneath that read: “Go, Perdita, Go!”

“She would continue that tradition of making T-shirts to cheer me on, like, forever,” Felicien said.

When it came time for the biggest moment of Felicien’s athletic career — the 2004 Athens Olympics — her mom wasn’t in the stands. Instead, she was watching back home in Ontario, surrounded by friends and family.

Felicien was widely expected to win gold in the 100-metre hurdles.

But in the final event, she caught her foot on the first hurdle and fell into an adjacent lane, knocking down her Russian competitor.

Back home, Felicien Browne says she felt a stab of grief, as if someone close to her had died. She blamed herself for pushing Felicien too hard. But most of all, she felt powerless.

“That’s the part that was killing me,” she said. “I just wish that I was there to hold on to her and tell her everything is going to be OK. But I was miles away from her.”

Felicien has spoken publicly about that moment many times over the last 17 years, always maintaining a stoic demeanour. But as her mom described her feelings, Felicien began to cry.

“I think the hardest thing for me in that moment was I needed someone to just help orient me. And I had no one,” she said.

She says she tried to leave the track to seek comfort from some nearby friends, but the Olympic official wouldn’t allow it.

“I remember having the smallest voice and pleading with this man just to help me. And I said, ‘I just need a hug. I just need a hug.’ And he wouldn’t let me pass,” she said, her muffled tears turning into sobs.

She wouldn’t feel relief again until she was able to call her mother. Felicien Browne told her daughter: “Do not cry. Don’t shed no tears. You are the gold.”

“To this day, that gives me comfort,” Felicien said.

Felicien never realized her dream of winning an Olympic medal. She was supposed to compete at the 2008 Summer Games in Beijing, but was sidelined by an injury.

But a new door opened when CBC Television asked her to travel to Beijing as a guest commentator.

“It felt so strange to go and be asked to do commentary on a race that I felt that I could have won, I could have been in. And here I am, another Olympic letdown, an epic fail,” she said.

“But I went, and the 10 days that I spent in Beijing, had I not said yes, I don’t know that I would have discovered what I was meant to do in this next chapter.”

Now she has a daughter of her own, two-year-old Nova.

“I have realized that I come from a strong lineage of women,” she said.

“The reason my mother could take the chances that she took in Canada by herself is because my grandmother, her mother said, ‘You go and see what you can see.’

“And so now I look at what I’ve seen because of my grandmother and my mother. And I think of what Nova has already seen, and what she will see, what she will do.”

Original story on CBC’s “As It Happens” appears here.